How much of history do we remember? As a philosopher once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. But we keep forgetting and thereby keep repeating the same mistakes. Our collective history is littered with examples of the vilest of deeds that have repeated themselves through the ages. From Germany to Gujarat and from Rwanda to Cambodia millions have been murdered and massacred just because they were the ‘other’. A group of ‘others’ who could conveniently be blamed for whatever imaginary wrongs those in power could propagate about them. And people would believe them for it is easier to blame someone else rather than confront a problem.

Therefore, it is important to create symbols and to build special places where memories of the past are kept alive and remembered. For it is necessary to remember even if memories seem futile. For in remembering we make a promise even if we do not always keep it. A promise to do whatever it takes to prevent what we are seeing of the past from repeating itself in the present or in the future.

One such place is the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Among the museums I’ve seen it alone makes brilliant use of light and space to evoke a feeling of great loss and sadness. Each facet of the architecture and arrangement is meant to mean something and that meaning is conveyed using the simplest of means: stark unadorned walls, huge empty rooms, select photos and belongings, uneven ground, all meant to reproduce at least in part the unbelievable horrors experienced by the victims of the holocaust.

The above photo is from an art installation called ‘Fallen Leaves’ inside the haunting Memory Void section of the museum by an Israeli artist. The artist actually requests visitors to walk on the faces made of metal. But somehow it was very very tough for me to do that. It felt as if I was walking on real people, as if I was stepping on the faces of actual people lying dead. And perhaps that was the artist’s intention all along.

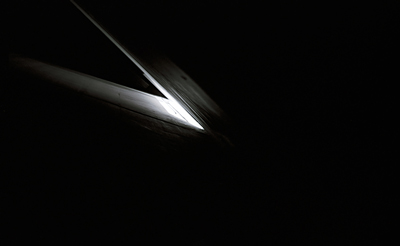

The museum is a great example for the strong impact minimalism makes. Unlike other museums it does not overwhelm you or crowd your thoughts out with an excess of display. On the contrary, it gives you time to formulate your thoughts, feel and experience a bit of the pain and horror. I was especially moved by the Holocaust Tower (photo above) which is a tall stark tower that is completely dark except for a thin streak of light that is allowed in from the top. You are enclosed in darkness with only a bright shaft of light streaming in from the top. The darkness is a space for solitude and reflection while the light above is perhaps the proverbial hope at the end of the tunnel. The Garden of Exile and Emigration (photo below) is another place that affects you through the ingenious use of uneven ground and inclination to disturb you and create a sense of imbalance. An imbalance that is upsetting and disorientating and meant to evoke what it feels to be in exile.

Architecturally, the museum is one of my favorite buildings and the genius of Daniel Libeskind, the architect, must be appreciated. The building is a work of art in itself. If you do get to go to the museum (if you are in Berlin do not miss going there) go there alone if you can for this is something that needs to be taken in on your own. What you feel and experience there will stay with you for a lifetime.