Villagers in Central India Set an Example for Conservation at the Community Level

(Note: First published here.)

Say no to establishment of a lime kiln to protect a reserve forest

Located in Madhya Pradesh’s Mandla district, Bagaspur is a pilot village where WWF-India is working with the villagers to conserve wildlife for the past six years. It is located inside Central India’s Satpura Maikal landscape, which is home to approximately 13% of the world’s wild tiger population. Among the issues facing the landscape are over-exploitation of the natural resources, particularly the wood from the forests. To overcome these, WWF-India has facilitated formation of a village level Forest Conservation Committee that sustainably manages the nearby reserve forest.

© SML Mandla Office/ WWF-India

A photo of a lime kiln

Overcoming the lure to make a few quick bucks

A few months ago, in 2010, the villagers of Bagaspur were approached by a lime kiln owner from a nearby village who promised them money to develop the village and construct the village road. He even offered to construct a temple for their use. In return he wanted the villagers to let him open a lime kiln in the village He had secured the required permission from forest department to source the wood from the surrounding reserve forest.

The villagers realized that the heating requirements of a lime kiln for a five day period were 2 – 3 truck loads of wood. The lime kiln owner had an assured supply of only a truck load of wood with the permissions in place. He wanted the villagers to source the remaining wood requirements from the reserve forest, illegally! He offered to pay for such illegally collected wood. The villagers, however, were against even sourcing fallen branches for the kiln from the forest, let alone felling green trees for wood on such a scale. They refused straight away.

© SML Mandla Office/ WWF-India

The reserve forest around Bagaspur village

Support to villagers by WWF-India’s field team

Undeterred by the refusal of the villagers the lime kiln owner then approached Girish Patel, part of the SML team at WWF-India’s Mandla field office, and offered to pay him if he could convince the villagers in agreeing to set up the kiln. But Girish also refused point blank. As he recalls, “I felt the villagers had rights over the reserve forest although not for illegal cutting for commercial purpose.”

When Girish also rejected the offer, the lime kiln owner even threatened him with dire consequences if he did not change his mind. However, both Girish and the villagers remained steadfast in their refusal and the kiln owner had to abandon his plans.

Girish says from his past experience that had this kiln been allowed to come up then many more kilns would have come up within a short space of time in the surrounding villages like Pauri, Thangul, Umaria to name a few, which would have led to rapid degradation of the reserve forest in the area.

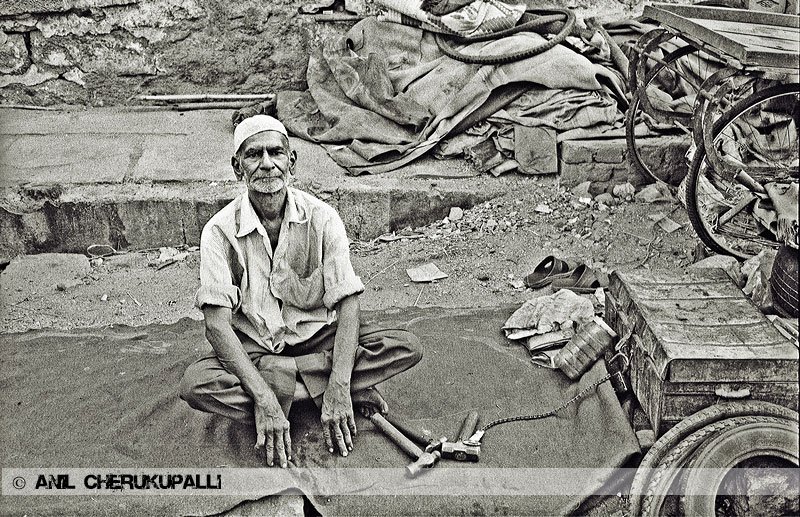

© SML Mandla Office/ WWF-India

Villagers of Bagaspur meeting with WWF-India field staff

The villagers also wrote a letter to the district collector requesting him not to allow such a lime kiln to come up in their village.

As Mr. Sumeri Lal Marathi, President of Bagaspur’s Forest Conservation Committee concluded, “We, the villagers of Bagaspur, refused the proposed lime kiln as increased cutting of wood over the years would have lead to the erosion of the natural resources from the forest on which we all are dependant.”

By forgoing short terms gains for long term conservation needs, the villagers of Bagaspur have set an inspiring example.