The liberalisation of India’s economy was adopted by India in 1991. Facing a severe economic crisis, India approached the IMF for a loan, and the IMF granted what is called a ‘structural adjustment’ loan, which is a loan with certain conditions attached which relate to a structural change in the economy. The government ushered in a new era of economic reforms based on these conditions. These reforms (broadly called Liberalisation by the Indian media) can be broadly classified into three areas: Liberalisation, privatization and globalization. Essentially, the reforms sought to gradually phase out government control of the market (liberalisation), privatize public sector organizations (privatization), and reduce export subsidies and import barriers to enable free trade (globalization). There was a considerable amount of debate in India at the time of the introduction of the reforms, it being a dramatic departure from the protectionist, socialist nature of the Indian economy up until then. However, reforms in the agricultural sector in particular came under severe criticism in the late 1990s, when 221 farmers in the south Indian state of Andhra Pradesh committed suicide. (The damage done, 2005) The trend was noticed in several other states, and the figure today, according to a leading journalist and activist, P. Sainath1, stands at 100,000 across the country. (Sainath, 2006) Coupled with this was a sharp drop in agricultural growth from 4.69% in 1991 to 2.06% in 1997. (Agriculture Statistics at a Glance, 2006) This paper seeks to look into these and other similar negative trends in Indian agriculture today, and in analyzing the causes, will look at the extent to which liberalisation reforms have contributed to its current condition. It will look at supporting data from three Indian states which have been badly affected by the crisis: Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Kerala. Andhra Pradesh’s (AP’s) experience is particularly critical in this debate because it was headed by Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu, who pursued liberalization with enthusiasm. Hence liberalization in AP has been faster than other states, and the extent of its impact has been wider and deeper. (Sainath, 2005)

Indian Agriculture today: A Snapshot

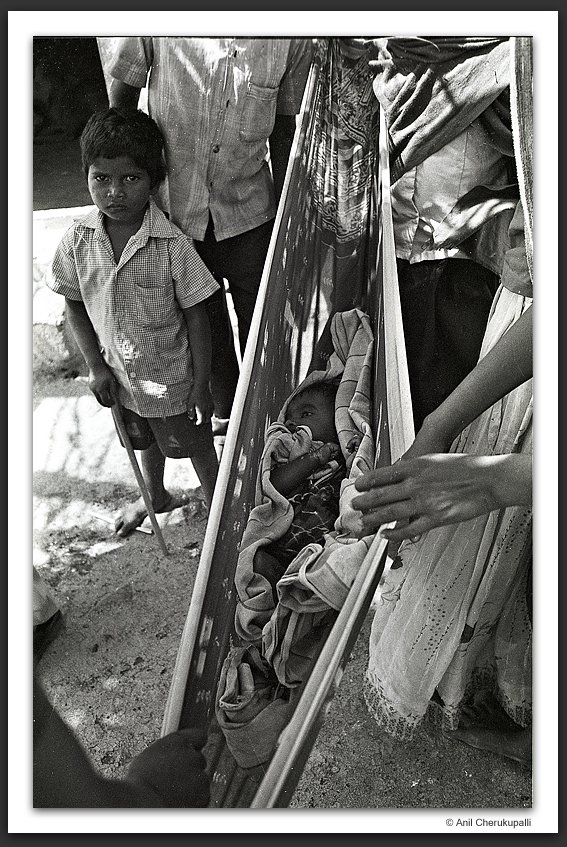

Agriculture employs 60% of the Indian population today, yet it contributes only 20.6% to the GDP. (Isaac, 2005) Agricultural production fell by 12.6% in 2003, one of the sharpest drops in independent India’s history. Agricultural growth slowed from 4.69% in 1991 to 2.6% in 1997-1998 and to 1.1% in 2002-2003. (Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2006) This slowdown in agriculture is in contrast to the 6% growth rate of the Indian economy for almost the whole of the past decade. Farmer suicides were 12% of the total suicides in the country in 2000, the highest ever in independent India’s history. (Unofficial estimates put them as high as 100,000 across the country, while government estimates are much lower at 25,000. This is largely because only those who hold the title of land in their names are considered farmers, and this ignores women farmers who rarely hold land titles, and other family members who run the farms.) (Sainath, P) Agricultural wages even today are $1.5 – $2.0 a day, some of the lowest in the world. (Issac, 2005) Institutional credit (or regulated credit) accounts for only 20% of credit taken among small and marginal farmers in rural areas, with the remaining being provided by private moneylenders who charge interest rates as high as 24% a month. (Sainath, 2005) An NSSO2 survey in 2005 found that 66% of all farm households own less than one hectare of land. It also found that 48.6% of all farmer households are in debt. The same year, a report by the Commission of Farmer’s welfare in Andhra Pradesh concluded that agriculture in the state was in ‘an advanced stage of crisis’, the most extreme manifestation of which was the rise in suicides among farmers. Given the performance of agriculture and figures of farmer suicides across the country, this can be said to apply to Indian agriculture as a whole.

The Crisis facing Indian Agriculture

The biggest problem Indian agriculture faces today and the number one cause of farmer suicides is debt. Forcing farmers into a debt trap are soaring input costs, the plummeting price of produce and a lack of proper credit facilities, which makes farmers turn to private moneylenders who charge exorbitant rates of interest. In order to repay these debts, farmers borrow again and get caught in a debt trap. I will examine each one these causes which led to the current crisis in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Maharashtra, and analyse the role that liberalisation policies have played.

As was mentioned earlier, AP’s experience is particularly relevant in this analysis because of its leadership. Let me explain in detail. Chandrababu Naidu, Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh from 1995-2004, was an IT savvy neo-liberal, and believed that the way to lead Andhra Pradesh into the future was through technology and an IT revolution. His zeal led to the first ever state level (as opposed to national level) agreement with the World Bank, which entailed a loan of USD 830 million (AUD 1 billion) in exchange to a series of reforms in AP’s industry and government. Naidu envisaged corporate style agriculture in AP, and implemented World Bank liberalisation policies with great enthusiasm and gusto. He drew severe criticism from opponents, saying he was using AP as a laboratory for extreme neo-liberal experiments. Hence, AP’s experience with liberalization is critical.

The Debt Trap and the Role of Liberalisation

The Debt trap: High Input Costs

Seeds:

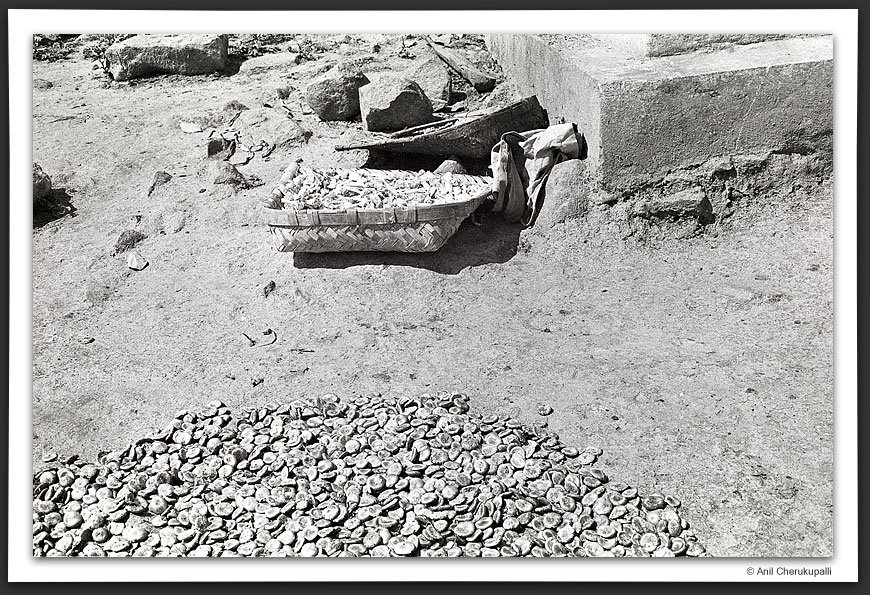

The biggest input for farmers is seeds. Before liberalisation, farmers across the country had access to seeds from state government institutions. For example, AP’s APSSDC3 produced its own seeds, was responsible for their quality and price, and had a statutory duty to ensure seeds were supplied to all regions in the state, no matter how remote. The seed market was well regulated, and this ensured quality in privately sold seeds too. (The damage done, 2005) With liberalization, India’s seed market was opened up to global agribusinesses like Monsanto, Cargill and Syn Genta. Also, following the deregulation guidelines of the IMF, 14 of the 24 units of the APSSDC’s seed processing units were closed down in 2003, with similar closures in other states. This hit farmers doubly hard: in an unregulated market, seed prices shot up, and fake seeds made an appearance in a big way. Seed cost per acre in 1991 was Rs. 70 (AUD 2) but in 2005, after the dismantling of APSSDC and other similar organizations, the price jumped to Rs. 1000 (AUD 28), a hike of 1428%, with the cost of genetically modified pest resistant seeds like Monsanto’s BT Cotton costing Rs. 3200 or more per acre, (AUD 91) a hike of 3555%. (Sainath, 2005) BT Cotton is cotton seed that is genetically modified to resist pests, the success of which is disputed: farmers in Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra now claim that yields are far lower than promised by Monsanto, and there are fears that pests are developing resistance to the seeds. (Menon & Jayaraman, 2002) Expecting high yields, farmers invest heavily in such seeds. Also BT Cotton and other new seeds guarantee a much lower germination rate of 65% as opposed to a 90% rate of state certified seeds. Hence 35% of the farmer’s investment in seeds is a waste. (Sainath, 2004) Output is not commensurate with the heavy investment in the seeds, and farmers are pushed into debt. The abundant availability of spurious seeds is another problem which leads to crop failures. Either tempted by their lower price, or unable to discern the difference, farmers invest heavily in these seeds, and again, low output pushes them into debt. Earlier, farmers could save a part of the harvest and use the seeds for the next cultivation, but some genetically modified seeds, known as Terminator, prevent harvested seeds from germinating, hence forcing the farmers to invest in them every season.

Fertilizer and Pesticide:

One measure of the liberalisation policy which had an immediate adverse effect on farmers was the devaluation of the Indian Rupee in 1991 by 25% (an explicit condition of the IMF loan). Indian crops became very cheap and attractive in the global market, and led to an export drive. Farmers were encouraged to shift from growing a mixture of traditional crops to export oriented ‘cash crops’ like chilli, cotton and tobacco. (The damage done, 2005) These need far more inputs of pesticide, fertilizer and water than traditional crops. Liberalisation policies reduced pesticide subsidy (another explicit condition of the IMF agreement) by two thirds by 2000. Farmers in Maharashtra who spent Rs. 90 an acre (AUD 2.5) now spend between Rs. 1000 and 3000 (AUD 28.5 – 85) representing a hike of 1000% to 3333%. Fertilizer prices have increased 300% (Sainath, 2005) Electricity tariffs have also been increased: in Andhra Pradesh tariff was increased 5 times between 1998 and 2003. (Seeds of ruin, 2005) Pre-liberalisation, subsidised electricity was a success, allowing farmers to keep costs of production low. These costs increased dramatically when farmers turned to cultivation of cash crops, needing more water, hence more water pumps and higher consumption of electricity. Andhra Pradesh being traditionally drought prone worsened the situation. This caused huge, unsustainable losses for the Andhra Pradesh State Electricity Board, which increased tariffs. (This was initiated by Chandrababu Naidu in partnership with Britain’s DFID4 and the World Bank.) Also, the fact that only 39% of India’s cultivable land is irrigated makes cultivation of cash crops largely unviable, but export oriented liberalisation policies and seed companies looking for profits continue to push farmers in that direction. (Isaac, 2005)

The Debt Trap: Low price of Output

With a view to open India’s markets, the liberalization reforms also withdrew tariffs and duties on imports, which protect and encourage domestic industry. By 2001, India completely removed restrictions on imports of almost 1,500 items including food. (The damage done, 2005) As a result, cheap imports flooded the market, pushing prices of crops like cotton and pepper down. Import tariffs on cotton now stand between 0 – 10%, encouraging imports into the country. This excess supply of cotton in the market led cotton prices to crash more than 60% since 1995. As a result, most of the farmer suicides in Maharashtra were concentrated in the cotton belt till 2003 (after which paddy farmers followed the suicide trend). (Hardikar, 2006). Similarly, Kerala, which is world renowned for pepper, has suffered as a result of 0% duty on imports of pepper from SAARC5 countries. Pepper, which sold at Rs. 27,000 a quintal (AUD 771) in 1998, crashed to Rs. 5000 (AUD 142) in 2004, a decline of 81%. As a result, Indian exports of pepper fell 31% in 2003 from the previous year. (Sainath, 2005) Combined with this, drought and crop failure has hit the pepper farmers of Kerala hard, and have forced them into a debt trap. Close to 50% of suicides among Kerala’s farmers have been in pepper producing districts. (Mohankumar & Sharma, 2006)

The Debt Trap: Lack of credit facilities and dependence on private money lenders.

In 1969, major Indian banks were nationalized, and priority was given to agrarian credit which was hitherto severely neglected. However, with liberalisation, efficiency being of utmost importance, such lending was deemed as being low-profit and inefficient, and credit extended to farmers was reduced dramatically, falling to 10.3% in 2001 against a recommended target of 18%. (Seeds of ruin, 2005) A lack of rural infrastructure deters private banks from setting up rural branches, with the responsibility falling on the government, which has reduced rural spending as a result of its liberalisation policies. Rural development expenditure, which averaged 14.5% of GDP during 1985 – 1990 was reduced to 8% by 1998, and further to 6% since then. This at a time when agriculture was going through a crisis proved disastrous for farmers, who turned to private money lenders who charge exorbitant rates of interest, sometimes up to 24% a month. (Seeds of Suicide, 2005) With input costs and output prices being what they are, coupled with crop failures and drought, they are pushed into debt which is impossible to repay. 12 out of India’s 28 states have 50% and higher indebtedness among farm households. Andhra Pradesh has the highest percentage of indebted farm households — 82%. 64.4% of Kerala’s farm households and 54.8% of Maharashtra’s farm households are indebted (NSSO, 2003) Indebtedness has been identified as the single major cause of suicides in both Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Maharashtra. (Analysis of Farmer Suicides in Kerala, 2006, Who’s suicide is it anyway, 2005, Saving small farmers, 2005)

Liberalisation and how it Failed

Branco Milanovic, a World Bank economist describes how he believes liberalisation helps developing countries achieve growth: ‘when a country lowers trade barriers, reduces government intervention in the market in order to allow market forces to operate freely, increases competition and attracts foreign investment, it will increase productivity and reduce inefficiency, which will lead to economic growth, and in a few generations, if not less, the poor will become rich, illiteracy will disappear, and poor countries will catch up with the rich.’ (The damage done, 2005) This argument is an economic rationalist one, which views government intervention with profound suspicion, and has equally profound faith in unfettered market forces. (Whitwell quoting Robert Manne, 1998) What Mr. Milanovic neglects to mention, though, is that rich countries which now preach liberalisation protected their ‘infant industries’ at the time they began to industrialize, till they were strong enough to compete globally. The US government, for example, had a protectionist trade policy in the late nineteenth century to help US companies become competitive in the world. Besides, apart from wool, the US, Germany, Britain and France were all almost self-sufficient in the raw materials that they needed for industrialization, and took off from that platform, a luxury that India and other developing countries do not have. (Issac, 2005) As German economist Friedrich List says, the adoption of these values (of liberalisation) assumes that all countries are at the same starting place, which (as we have seen above) is clearly not the case. (Issac, 2005) In fact, it is this very reason that has brought about the crisis that Indian agriculture is facing today. Most farmers in India were already in a position of minimum security, with no education system, credit facilities, access to alternative employment, or efficient technology. Their only support was government subsidy and regulation. Liberalisation policies came in and dismantled their only support structure. It halted the sharp reduction in rural poverty from 55% in the 1970s to 34% in the 1980s. Not only has the incidence of poverty in rural areas not gone lower than 34% in the 1990s, it has gone to higher levels of 42% in individual years. (Ghosh, 2000)

The second most popular argument of the economic rationalists in favour of liberalisation is that competition will weed out the inefficient, and in the growth that ensues, employment will be provided in other areas of the economy, thus lifting the poor out of poverty. This argument however assumes that the poor will be able to take advantage of the opportunities presented to them. As Robert Issac says in ‘The Globalization Gap’, “Globalization encourages the well positioned to use tools of economics and politics to exploit market opportunities, boost technical productivity, and maximize short-term material interests.” This is compounded in India, where the gap between one who is ‘well positioned’ and one who is not can be extreme. With a lack of investment, chances of generation of rural employment are slim. Unemployment and underemployment are chronic problems in India, with the rate of unemployment being close to 10% in 2004. (Sainath, 2005) Primary education in rural areas is mismanaged and bad quality, and there is no system which helps agricultural workers find alternate employment, or develop alternate skills. (Chossudovskly, 1997) In the face of such obstacles, it is nearly impossible to expect agricultural workers to shift to alternate fields. Coming back to AP, the IT Revolution spearheaded by Chandrababu Naidu attracted companies like Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Dell and created thousands of jobs. However, given the skills and education of most farmers, it is obvious that none of this translated into job opportunities for them.

The final argument that supporters of globalization have is the much touted 10% reduction in poverty (60 million decline in poor) in India in the year 2000. However, this figure was challenged by experts. Poverty is defined according to how many people consume less than the nutritional minimum prescribed. (2400 calories for rural areas, and 2100 for urban areas) Major changes in survey design in 1999-2000 not only made the resultant estimates incomparable to previous years’ estimates, but an over-estimation of consumption (meaning people were getting enough food, hence were not considered poor) meant a sharp reduction in poverty figures. After experts challenged it, the Planning Commission of India accepted that the figure was inaccurate, and could not be compared to previous years’ estimates, hence the 10% drop in poverty is incorrect. With adjusted figures, experts have determined that the decrease in poverty was a mere 2.3%, and that the number of poor increased by nine million in 2002 as compared to 1999.

Liberalization and ‘Growth’

Many economists now concede that the relationship between liberalisation and growth are ‘uncertain at best’. According to the Center for Economic and Policy research, which studied impact of liberalisation reforms on the developing world, key economic and social indicators such as increases in life expectancy, infant and child mortality, education and literacy levels slowed down in the 20 years between 1980 and 2000 when liberalisation policies were implemented, compared to the 20 years leading to 1980. (The damage done, 2005) This defeats the economic rationalist argument of free trade eliminating poverty, since the 20 years leading up to 1980 witnessed high protectionist policies and trade barriers. Following the suicides in 2000, the World Bank and Britain’s DFID abandoned power reforms in Andhra Pradesh four years before schedule. It admitted that it had ‘substantially underestimated’ the ‘complexity of the process’ and that there must be ‘increased consultation with the farmers to get their acceptance’ of any further reform. (The damage done, 2005).

The Andhra Pradesh government sponsored report by the Commission of Farmer’s Welfare squarely laid the blame for its agrarian crisis on the state and central government’s policies: “While the causes of this crisis are complex and manifold, they are they are dominantly related to public policy. The economic strategy of the past decade at both central government and state government levels has systematically reduced the protection afforded to farmers and exposed them to market volatility and private profiteering without adequate regulation; has reduced critical forms of public expenditure; has destroyed important public institutions, and has not adequately generated other non-agricultural economic activities.” A report on suicides in Kerala similarly held the liberalization policies of the government responsible. (Mohankumar & Sharma, 2006)

Conclusion

It is clear that the liberalisation policies adopted by the government of India played a dominant role in the agrarian crisis that is now being played out. However, this is not to say that privatisation, liberalisation and globalization are per say bad, or inherently inimical to an economy. It is the ‘one size fits all’ brand of liberalisation adopted by the IMF and the World Bank which forces countries to privatize, liberalise and globalize without exception which has failed. Without taking into account the state of an economy, and in this case, the state and nature of the agricultural sector in India, the IMF and the World Bank, with the cooperation of the Indian government, embarked on mismatched reforms, which have caused misery and despair among millions of Indian farmers, driving large numbers of them to suicide. It is also essential to break the link between aid and liberalisation, which caused India in the first place to accept the conditions of the IMF. Remember that India was on the brink of a financial crisis in 1991 when it applied for the IMF loan and accepted its conditions—perhaps the course of economic reform in India would have taken a very different course if there was no urgent need to borrow from the IMF. The start to this process may have already occurred: recognizing the failure of its liberalisation policies, (and perhaps also the failure of DFID with AP’s power reforms) the Blair government of Britain announced in 2004 that it will no longer make liberalisation and privatization conditions of aid. In another blow to the neo-liberal lobby, Chandrababu Naidu suffered the worst ever defeat in the 2004 state elections in his party’s history, with rural AP clearly rejecting his brand of World Bank sponsored liberalisation. The battle, however, has not yet been won. It is essential for the rest of the G8 to follow Britain’s example in order to influence World Bank and IMF policy towards India to ensure blind liberalization is not pursued, and so that countries like India can adopt tailor-made reforms to suit their economy.

References

‘Agricultural Statistics at a Glance’, Indian Farmers Fertilizer Co-operative Limited, New Delhi, August 2004.

Chossudovsky, M 1997, The globalization of poverty: Impacts of IMF and World Bank Reforms, Zed Books Ltd., New Jersey & Third World Network, Penang.

Ghosh, J & Chandrasekhar, CP 2005, ‘The burden of farmers debt’ Macroscan, September 14, 2005

http://www.macroscan.org/fet/sep05/fet140905Farmers_Debt.htm

Ghosh, J 2000, ‘Poverty amidst plenty?’, Frontline, Volume 17 – Issue 05, March 04 – 17, 2000

Hardikar J, 2006 ‘The rising import of suicides’, India together, viewed June 10, 2006

http://www.indiatogether.org/2006/jun/opi-cotton.htm

Issac, R 2005, ‘The globalization gap’, Pearson Education Inc., New Jersey.

Land and Livestock Holdings Survey, NSS Forty-Eighth Round, 1991, Government of India.

Mohankumar, S & Sharma, RK 2006, ‘Analysis of farmer suicides in Kerala’, Economic and Political Weekly, April 22, 2006.

Sainath, P 2005, ‘No lessons from past mistakes’, The Hindustan Times, viewed 4 June, 2006.

http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/specials/farmersuicide/index.shtml

Sainath, P 2004 ‘Seeds of suicide’, The Hindu, July 20, 2004.

Sainath, P 2005 ‘As you sow, so shall you weep’ The Hindu, May 30, 2005.

Sainath, P 2005, ‘Spice of life carries whiff of death’, The Hindu, February 13, 2005.

Sainath, P 2004 ‘Dreaming of water, drowning in debt’, The Hindu, July 18, 2004.

‘Seeds of ruin’, The Indian Express, July 3, 2005.

‘The damage done: aid, death and dogma’, May 2005, Christian Aid.

www.christian-aid.org.uk/ indepth/505caweek/CAW%20report.pdf

Whitwell, G 1998, ‘What is economic rationalism’, ABC, viewed June 10, 2006

http://www.abc.net.au/money/currency/features/feat11.htm#fn1

‘Whose suicide is it anyway’, Indian Express, June 23, 2005.

[-] Show Less