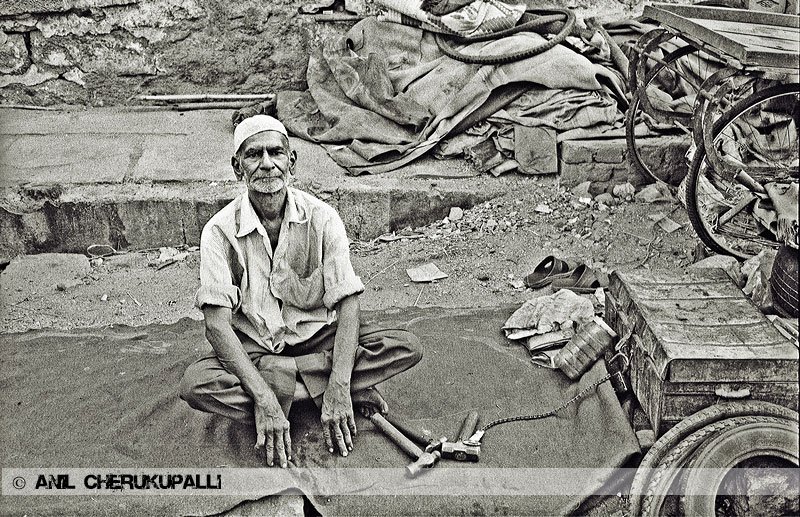

Udaipur

December 2010, Udaipur.

December 2010, Udaipur.

(Note: First published here.)

Report by WWF-India highlights threat by proposed railway line expansion to crucial corridor linking tiger habitats.

Kanha-Pench tiger corridor

Located in the Central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, the Kanha-Pench corridor is one of the most important forest corridors in India and facilitates tiger dispersal between Kanha and Pench Tiger Reserves. It covers an area of 16,000 sq km and acts as a refuge for several other mammals such as wild dogs, sloth bear, leopard, hyena, jackal, and sambar to name a few. The Kanha-Pench Corridor also harbours gaur and is known to facilitate their movement. The presence in the corridor of wild prey such as gaur, sambar, chital can help prevent killing of cattle by tigers and thus prevent retaliatory conflict with locals.

Importance of corridors

Sub-adult male tigers are forced to move out of areas where they are born and find new territories. These dispersing sub-adult males are often the ones that manage to use a corridor and get to the adjacent protected area.

A tiger passing through a corridor forest has to confront a range of challenges such as hostile villagers, retaliatory poisoning of livestock kills, poaching of tigers and prey, electrocution by live wires, apart from road and rail traffic. The widening of railway lines and construction and widening of roads in such a corridor will result in fragmentation of the corridor and thereby make dispersal all the more difficult for tigers and other animals that use the corridor.

Such corridors are vital for the long term survival and viability of tigers as they connect smaller tiger populations (eg. Pench and Achanakmar) to larger source populations such as Kanha. Without these linkages tiger populations isolated within individual tiger reserves face the risk of extinction due to poaching and loss in genetic vigour over generations.

© WWF-India

2009, Hyderabad

In an instant

I’m plunged into

the old roaring of words

that fell from the soaring heights of

our eyes

to land like rainbow colored mist between

our toes.

—-

This geography

of eyelashes and elbows

making its mark

on our common spaces.

—-

The unchanged arc

of our intimate history

lights up

your single dimple.

——

The fog is thick between

the dust colored sunshine

and the fading smell

of last night’s jasmine.

—–

Leave this hour behind

inside me

like the signature of your smile

on the blind tips of my fingers.

My first short film for WWF:

This short film provides an overview on how the technique of camera trapping is used to estimate tiger numbers and how this aids in tiger conservation.

This film can also be seen on WWF-India’s YouTube channel here.

Gangtok, Sikkim.

First, a belated Happy New Year to everyone! Hope you have a wonderful year ahead. It has been a really long time since my last post here. Hopefully, I’ll be more regular with my posting from now on.

(Note: First published on WWF-India’s website)

A rare beauty

Known for the beauty of its reddish-orange coat and white ‘teardrops’ falling away from its eyes, the red panda (Ailurus fulgens) is found in parts of Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Southern China and India. In India, it is found in the states of Sikkim, northern West Bengal, Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh, where a majority of its population occurs. Classified as a Vulnerable species by IUCN*, increasing habitat loss poses a major threat to its survival. WWF-India is currently working with its stake holders to conserve this rare animal in most of its distribution range across North East India.

Communities for nature

Since 1992, WWF-India has partnered with local villagers, Indian Army and Forest Department in the Western Arunachal Landscape (WAL), which covers nearly 7000 sq. km. area of Tawang and West Kameng districts, to conserve its rich biological diversity. The maximum forest area in WAL is under the customary tenure of local indigenous communities. WWF-India facilitated the establishment of Community Conserved Areas (CCA) in 2004 to ensure sustainable management and community protection of such forests that also form the habitat of the red panda.

One such CCA is the Pangchen Lumpo Muchat CCA, which comprises of Lumpo and Muchat villages. According to Nawang Chota, Secretary of Pangchen Lumpo Muchat CCA, “After the formation of the CCA we stopped hunting and fishing in it, and prevented outsiders from indulging in these as well. We also started community based tourism to provide a source of income to the villagers.”

In November 2010, three other villages – Socktsen, Kharman and Kelengteng, came together to form the Pangchen Socktsen Lakhar CCA. Together the two CCAs control 200 sq. km. of area. The wide variety of wildlife found in these forests includes the red panda. While formation of the CCAs stopped the hunting of wild animals, the continued loss of habitat posed a threat to the long term survival of the red panda. To prevent this, villagers from the two CCAs came together to form the unique Pangchen Red Panda Conservation Alliance with the support of Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and WWF-India. The aim of this community initiative is to help red panda conservation not only by banning its hunting or capture, but also by preventing the habitat loss and protecting the plant species on which it is dependent.

By preventing habitat loss the alliance also hopes to reduce human-wildlife conflict caused by wild animals such as wild boar, porcupines and monkeys raiding crops and villages. A Yak dung briquette unit is also under construction in the area to reduce fuel wood consumption and provide additional income. In addition, Pangchen Tourism Package involving five villages from the two CCAs is being developed to attract tourists and thereby provide an alternate source of livelihood for the locals.

WWF-India’s continuing support

Pijush Dutta, Landscape Coordinator, WAL, WWF-India said, “With this one of a kind initiative it is hoped that conservation of red pandas can be undertaken in a scientific manner with proper records maintained of sightings by villagers. The next step is to prepare a detailed master plan in consultation with the villagers for the management of the forests in a sustainable manner”.

“WWF-India will support this Conservation Alliance by undertaking a biodiversity documentation of the CCAs, conducting training courses for the villagers for sustainable management of local forests and support community based tourism as a conservation incentive,” adds Pijush.

* Wang, X., Choudhury, A., Yonzon, P., Wozencraft, C. & Than Zaw 2008. Ailurus fulgens. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. . Downloaded on 09 December 2010.

There I lay open

on the examination table

all my parts neatly arranged

like a high school biology diagram.

My separated eyes

leaking blood

into my upturned palm.

My grey and white matter

mingling with the filtered contents

of my drooping kidneys.

My shriveled testicles

in the company

of my jaundiced tongue.

My constricted anus

ignoring the abuse

of my screaming lips.

My enlarged liver and my enraged pancreas

creating an identity crisis for

my depressed ears.

My sunburnt skin sloughed off

and arranged in small piles beside

the mutant glow of my bleached teeth.

My adrenals exchanging high fives

with the spliced end

of my sexy spleen.

My pretty green gall bladder

tangled up

in the chilly red of my arteries.

My throat cut off in mid-sentence

leaning against

my fragile funny bone.

My vacated heart

still pulsing and dripping

in the center.

And finally my central locking lever

standing aloof and awaiting deliverance

from an unsatisfied fuck lust

inside the rigor mortified fist

of my unfamiliar right hand.

The art of photo printing is slowly becoming archaic like a floppy drive or a cassette player. Nowadays, hardly anyone prints their digital photos, forget printing from film negatives. But not too long ago it was an art. It is still an art but the great practitioners of that art are slowly but steadily dying out. The intuition to judge the correct timing for development and fixing, the ability to extract detail from where it would seem impossible, correct mistakes made by the photographer and in the end produce a print that is virtually identical to the vision of the photographer is no mean task. But great printers are rarely given their due and most are content to toil in their darkrooms in search of that perfect print. It is therefore all the more important to celebrate one of the true artists in this field who printed for some of the very greats in photography. Reproduced below is an excerpt from one of the two lovingly written articles paying homage to Voja Mitrovic – one of the greatest printers in photography.

If you have even the slightest interest in photography, go grab a coffee, put your feet up and read the two articles (links after the excerpt) at your leisure.

Both Voja and Picto would have a tremendous impact on my own destiny. In June of 1979, after arriving back in Paris, I went to see Pierre Gassmann at Picto and asked for a job as a printer. Pierre, with his tough-love gruff voice, asked me what I knew how to do—and I exaggerated and told him that I was a great printer and knew how to do eve- rything with black-and-white prints. He said to me, “We will see. You will have a three day tryout, and if you aren’t as good as you say, you won’t get the job.” On my first day of my tryout, I was given 100 negatives and told to make 8×10-inch prints of each by the end of the day. At 4 p.m., a tall, handsome man with a foreign accent, one of the printers in the lab—Voja—came to my enlarger and asked how it was going. I told him that I had only printed 20 negatives. He said to me, “You will never get this job—give me the negatives.” I watched him take the hundred negatives to his enlarger, and in one hour, he printed the remaining 80 negatives, putting each sheet of printing paper in a closed drawer after exposing each negative. At 4:50 pm, he took out 80 sheets of exposed photographic paper and went to the open developing tank. I watched him chain develop all the prints, and one by one put all 80 prints, perfectly printed, into the fixer. At 5:10 p.m. that day, Pierre Gassmann walked into the lab and said, “letʼs see how you have done.” He put his foot on the foot pedal to light up the fixer tank with bright red light, and went through my 100 prints laying in the fixer-and a few seconds later, looked up and said to me, “you are as good as you said; you are hired!” After Gassmann walked out of the dark room, I took Voja aside, and said, “thank you. I will find a way one day to thank you for this!” He looked at me and said, “I was an immigrant also. I know what it means to need work—we need to help each other!”

—Copyright 2010 by Peter Turnley, Paris, France

Both the articles were written by Peter Turnley and were first published on Mike Johnston’s consistently excellent photography blog-The Online Photographer.

by Ameen Ahmed and Anil Cherukupalli

(Note: First published on WWF-India’s website. The following modified version appeared subsequently on WWF’s Global Intranet.)

Meet the Pardis

Hardly a community in India’s recent history has been more affected by changing laws and times than the Pardis. A nomadic tribe spread across the central states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, the Pardis have depended on forests for their livelihoods for countless generations. In particular, they hunt wildlife.

The erstwhile Maharajas, recognizing the Pardis’ considerable skills, employed them to drive wildlife toward the kings’ hunting parties. Many farmers in central India employed Pardis to guard against crop-raiding wild animals; the deal was that the Pardis could keep the meat of the animals they caught.

Within the Pardis community, there are divisions according to various occupations and hunting practices. For example, the Phaandiya Pardis hunt their quarry using a rope noose. The Teliya Pardis sell meat and oil extracted from reptiles they capture. But the most remarkable aspect of hunting by Pardis is their total dependence on traditional means and basic equipment, like rope, wooden clubs and knives, to bring down wildlife. They rarely use a search light, vehicles or guns.

Troubled times: post-Independence and the Wildlife Protection Act

The British treated most Pardis as social pariahs. Most of their sub-sects were included in the list of “criminal tribes” in the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Though the act was overturned after independence in 1952 and they were “de-notified,” the historical stigma remains.

Life for the Pardis took a dramatic turn for the worse in 1972, when the Indian government adopted the Wildlife Protection Act. Pardis were not only prohibited from entering many of the state-controlled lands, now designated as protected forests, national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, but overnight they were also required to stop hunting.