A Distant Summer

April 2007, Oia.

April 2007, Oia.

July 2007, Gerolstein.

March 2005, London.

Continuing with the theme of alternative sexualities…today’s front page lead story in the Bombay edition of the Sunday Times of India is interesting, to say the least.

Transgendered people in Tamil Nadu can now mark their sex as T in official documents instead of M and F. This is a real step forward in recognising the fact that there are people who define themselves outside the sexual binaries of ‘male’ and ‘female’.

Follow this link for the story, though I am afraid the full story is in the print edition.

Now, how long will it take for the next barrier to be breached? I am talking about article 377 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalises homosexuality. When will this relic from the raj era be struck down?

When I entered the living room, Krishnendu was in his usual place, sitting on the sofa with his face glued to his laptop and a cigarette clutched tight between his fingers. The circular turtle-backed ashtray on the coffee table in front of him was full of burnt out stubs. I mumbled a half-hearted hello. Krishnendu didn’t respond. He never did, at least not in the usual ways. He was glued to the screen, with a manic expression on his face. He was chatting online, one of his passions, and occasionally a hint of a smile would cross his face.

I had grown used to Khrishnendu’s moody ways over the course of the month that I stayed with them. Actually, he was my friend’s flat-mate. I was new to the city and was staying with them till I got my own accommodation. Krishnendu and Anand (my friend) worked in an NGO that worked among HIV affected groups. It was a community outreach NGO: by the community, of the community and for the community of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgendered people or LGBT. One of the stipulations of the NGO was that HIV positive people would constitute a certain percentage of its employees. Another was that it employed only gays.

The flat was a ten minute walk from their workplace and Anand had assured me that I could stay with them till I found my feet. It was a large, spacious house with two bedrooms, one for Krish and one for Anand. A young Nepali cook prepared the meals and flirted with the kirana girl downstairs when he went out on the pretext of grocery shopping every evening.

It was a good life and I slowly discovered the world of my flat mates. I used to be out on work all day and return late in the night exhausted, only to find my two mates along with office colleagues and assorted friends gathered around the mahogany coffee table in the living room. Anand would be in a ‘compromising’ position with ‘Indu’ (Indus actually) swigging cans of beer and making risque comments. “Arre, andar aati kya kothi,” he would hoot to cheers. “Abhi nahi re panthi, baad mein chalti hoon main,” they would reply (Kothi and panthi are terms used among MSMs to refer to the active and passive partners during sexual intercourse. The term kothi is an amalgamation of two words according to urban legend: kothi [Telugu for monkey] and kut [Persian for ass]. The first denotes friskiness or playfulness). Krish would be blowing out immaculate smoke rings clad in a white towel. The moment I entered all the men would wolf whistle and pass faux comments. Often Krish winked at me and indicated the bedroom. Sometimes they openly hinted that I should have sex with one of them. A deadpan expression or a lame joke was the only way out. But to be honest, I secretly enjoyed watching them interact, not least because their ‘world’ was a completely new experience for me, one that I hadn’t even imagined existed, let alone experienced.

It was uncomfortable being around Krish. He was not the most expressive person at the best of times. Silent, brooding, intense. Everyone walked on tiptoes around him. I knew that Krish valued his privacy and resented sharing his space with strangers. And though I shared a flat with him, I did not know anything about him apart from the bare bones: He was gay, he worked with MSMs (men who have sex with men) and he had AIDS.

Krish had contracted HIV seven years ago from one of his partners and it had developed into fullblown AIDS. The prevalence of AIDS is high among MSMs (almost three times the rate among lesbians). Though there is no known cure for AIDS yet, with proper care a patient can live for upto 10 years. Krish could have, if he took proper care of himself. He didn’t. He abused his body like there was no tomorrow. Apart from his chain smoking and binge drinking he never wore a shirt inside the flat, increasing his chances of contracting a chest infection. He never had his meals on time and when he did he nibbled at his food. He was oblivious to everyone’s pleadings that he look after himself.

March 2005, London.

We have borne in mind the object which the Amending Act wanted to achieve, namely…to provide easy access to the citizens of this country to live saving drugs and to discharge their constitutional obligation of providing good health care to its citizens.

With these words a Division Bench of the Madras High Court dismissed the petitions filed by multinational drug company Novartis against a key provision of the Indian Patents Act, 1970. The provision in question, called section 3(d) seeks to promote public access to affordable drugs by restricting the granting of frivolous patents on medicines.

Before I dive into the fascinating story of the politics behind public health let me briefly give a backgrounder to the ‘Gleevec issue’.

Gleevec is a drug used to treat a form of cancer called chronic myeloid leukemia. The drug was invented by the Swiss multinational drug company Novartis which has a patent for it. However, the Indian Patents Act of 1970 has provisions that grant ‘process patents’ and not ‘product patents’ (I shall explain the legalese later in this text). What this basically means is that companies could only obtain a patent for the process of manufacture and not on the final product itself. This enabled Indian pharmaceutical companies to reverse engineer the final products and discover new processes to manufacture them, thus giving rise to the generic industry. What this meant in practical terms is that India – thanks to domestic pharma companies that made generic versions of many of the multinational companies’ drugs – went from a net importer of drugs to a net exporter. By the same token, drugs which were overall expensive post-independence became cheap by the 1980s. In fact, global NGO’s working in the field of public health procure affordable drugs from India to use them in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

However, as a member of the WTO and a co-signatory of the TRIPS agreement India had to bring her domestic laws in compliance with international laws. It is in this context that the Gleevec controversy has to be examined.

It is an indictment of our media and society that important issues are given short shrift in favour of fluff and floss. The gleevec issue barely got a passing mention in the mainstream media.

And now we dive headlong into the chemical sludge…

In May 2006 Novartis AG and its Indian subsidiary, Novartis India (henceforth Novartis) filed a bunch of writ petitions before the Madras High Court claiming that section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act was contrary to the requirements of the TRIPS agreement and article 14 of the Indian constitution as it is vague and ambiguous. But what is section 3(d) about?

In a nutshell, 3(d) aims to prevent the practice called ‘evergreening’ by which drug companies seek to extend monopoly on their drugs by patenting minor variations of that chemical entity. Suppose a drug company has a patent on a chemical entity that is about to expire. What they will do is tweak the drug slightly and patent the new product(s). This guarantees that generics cannot be manufactured and that the patent is extended by another 20 years.

Section 3(d) was introduced into the 1970 Patents Act (the bedrock of Indian patents law and a progressive piece of legislation) via the Patents Amendment Act of 2005. This was done to meet India’s WTO obligations to grant product patents. Now, the 1970s Act granted only ‘process patents’ to agricultural and pharmaceutical products. Only the manufacturing process could be patented for 7 years and not the end product.

The case of Scarlette Keeling’s death in Goa is taking on epic proportions with accusations of cover-up and corruption leveled against the Goan police by Scarlette’s mother while the police seemingly shift from one position to another. First they said it was a case of death by drowning due to drug use in spite of the first autopsy detailing multiple signs of abuse on the girl’s body. After the second autopsy they changed the cause of death to rape and murder and then again flipped by falling back to their original position that it was actually death by drowning all along. Then they started claiming it was the fault of the girl’s mother to leave her alone in Goa while the former traveled elsewhere in India. And now, suddenly, the Goan police state that they have cracked the case with one of the prime suspects confessing to the rape and murder.

It is understandable why Fiona Mackeown, Scarlett’s mother, has no trust in the Goan police and wants a CBI probe. She alleges that the Goan police are in a criminal nexus with drug dealers and since the latter according to many reports are involved in the death of Scarlette she further claims that the police want to cover up the murder to protect the drug dealers. Another theory doing the rounds is that the Goan police wanted to hush up the murder as they did not want to damage Goa’s reputation as a prime tourist destination especially among Britons who comprise 60% of the foreigners visiting Goa.

Whichever way the case may finally turn what is undeniable is that it has completely tarnished the image of Goa and its police. In their bungled attempts to hush up the murder the Goan police have created a sordid news story that is going around the world. End result: Goa’s reputation as a ‘safe’ tourist paradise is under threat. Going wider it also threatens to silence the buzz generated by the ‘Incredible India’ tourist campaign. It is only recently that tourism in India has been growing at a strong pace increasing employment and injecting much needed money into the local economies. This case will only add to India’s unfortunate reputation that the rule of law exists only in name in India leading to tourists feeing unsafe and unprotected. One potential method to correct this would be for the Indian government to develop a special section among the police (that is accountable and transparent) to deal with crimes committed against tourists.

Unless the Goan police and the state government act quickly and take steps to restore confidence by punishing those police personnel involved in the cover up (the suspension of the one of the inspectors involved in the alleged cover up is a good first step) and pursue the criminals involved it is safe to speculate that tourist arrivals into Goa will take a hit. And underneath all the allegations and cover ups let us not forget the tragedy of a 15 year old girl who got involved with drugs and was killed while on holiday. While Fiona Mackeown might indeed have been irresponsible to leave her young daughter in the care of a tourist guide the least the Goan police can now do is to ensure that swift justice is delivered to her and her grieving family.

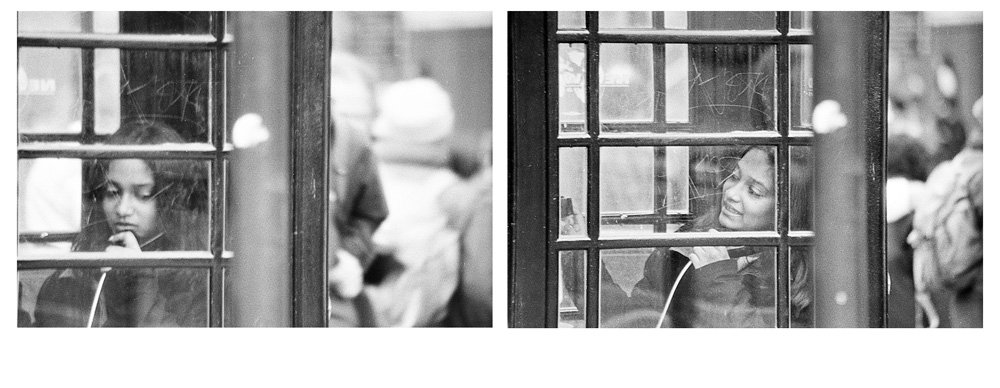

March 2005, London.

I was sorting through some old negatives and came across these two. As usual I screwed up the shots technically (in my defence didn’t know jack about cameras then) but I like the way the two photos play off each other.

November 2007, Cologne. (Fuji Sensia 100)

This is not a great shot. For one, the original exposure was way off (partially rescued here through post-processing). But I find the composition to be strangely peaceful and calming if such a thing is possible.